Floor

Sources have not provided any information about the original floor finish. Parquet would likely have been too expensive: there was a persistent lack of funds during the renovation. Wide pine floorboards were commonly used for formal spaces like this.

28cm-wide floorboards laid lengthwise were chosen for the reconstruction. It is unlikely that the floorboards stretched the entire length of the room – 13.5 metres – because planks that long would have been prohibitively expensive. This is why there are always two floorboards laid end to end in the reconstruction, with the join visible to the right of the entrance door.

The pine floor from 1680 in the Great Hall of Amerongen Castle. The pattern of the wood grain in these planks served as the model for the reconstruction.

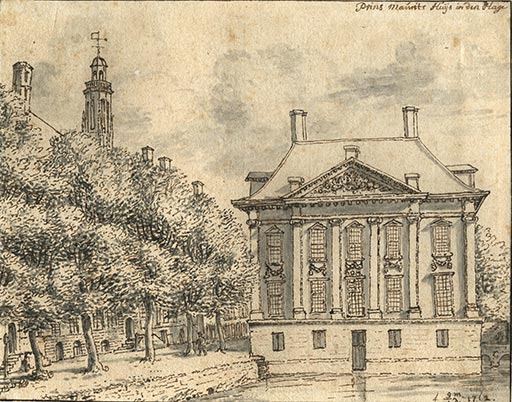

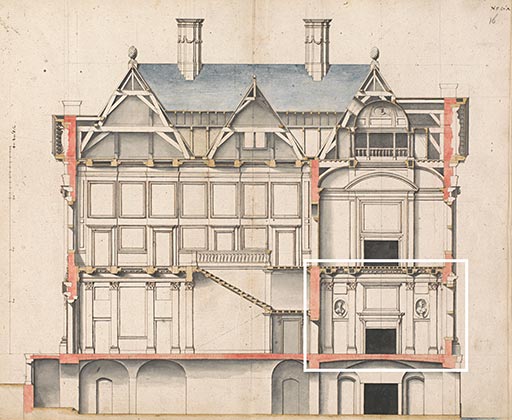

Cross section of the 17th-century Mauritshuis (National Library of the Netherlands, The Hague). The floor of the Golden Room rests on a stone vault, meaning that floorboards could be laid both widthways and lengthways.

Windows

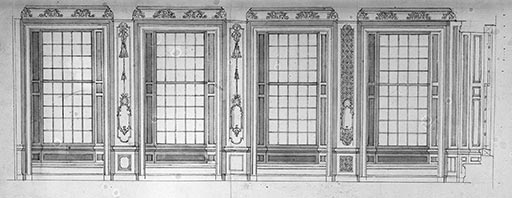

In the 17th century the Mauritshuis had crossbar window frames, as it does today. During the rebuilding of 1708-1718, it was given new sash windows divided into small panes according to the latest fashion. The lower part of the windows was made up of 5 x 5 panes, the upper part of 4 x 5 panes. This meant that the shutter panels fitted the windows perfectly.

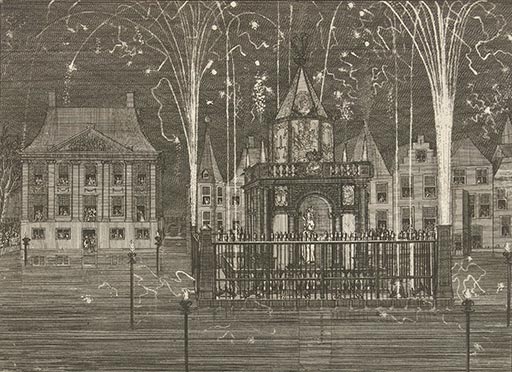

The sash windows appear on old prints, drawings and paintings of the Mauritshuis. The number of panes changes every time: the artists were clearly only giving an overall impression of the windows.

Window seats

Wooden seating within a window recess was a popular feature in formal interiors around 1700. The well-known architect and designer Daniël Marot (1661-1752) often incorporated it. Window seats appear, for example, in the Great Hall (c. 1717) of Duivenvoorde Castle (Voorschoten), which was possibly designed by Marot.

Door in window recess

The central window recess originally contained French doors. These are still visible in old prints, drawings and paintings. But there were no balcony railings. The doors were only replaced by windows in 1984. The seating in the window recess also dates from that year.

Ceiling

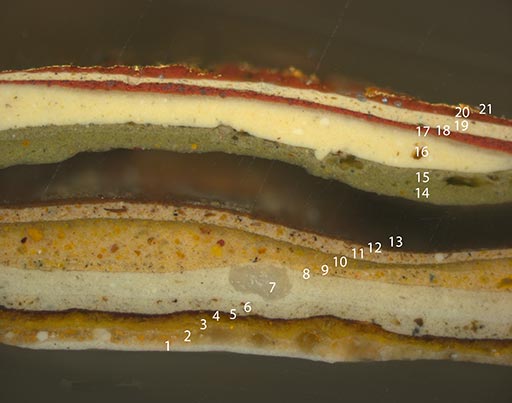

When the room was rebuilt, the ceiling was pale grey rather than white, just like the walls. It was embellished with brass leaf, for instance on the acanthus leaf decorations, the frames around the painted canvases and some of the mouldings. This original finish is now covered by a thick bed of later paint layers. But in cross sections of the paint, the brass leaf is still clearly visible.

Brass was a cheaper alternative to gold leaf. It was also used for the decorative details at the top of the walls, such as the capitals and the large ornament above the entrance door. The lower decorative details and painting frames were by contrast embellished with gold leaf.

Coving

The oak coving is today painted white, like the ceiling. Only the oak above the fireplace has been treated with lye. This makes it look like one part of the coving belongs to the ceiling and another to the walls: a confusing effect.

The coving was originally painted pale grey, making it part of both the ceiling and the walls. The carved corbels were decorated with brass leaf.

Capitals

The gilding on the capitals was only added in 1984. During the rebuilding of 1708-1718 the capitals were embellished with brass leaf. While gold never loses its lustre, brass becomes darker and tarnished over time. This meant that the brass elements were soon overpainted.

The present-day gilding sits on a thick bed of old paint layers. The uneven, rough surface gives it a rather scruffy appearance.

Pale grey walls

During the 1708-1718 rebuilding, the walls were painted pale grey. Here and there traces of this pale grey are still visible. The woodwork would have therefore had a ‘stone-like’ appearance.

For this reconstruction the decision was taken to show the grey as a uniform shade. But it is also possible that certain areas were a greener grey, like the front of the niches surrounding the grisailles.

Gilded decoration

The paintings’ frames and most of the carved woodwork on the walls were gilded. Walls in pale grey with gilded detailing was a popular decorative scheme for reception rooms in palaces and other notable buildings.

Carved decoration

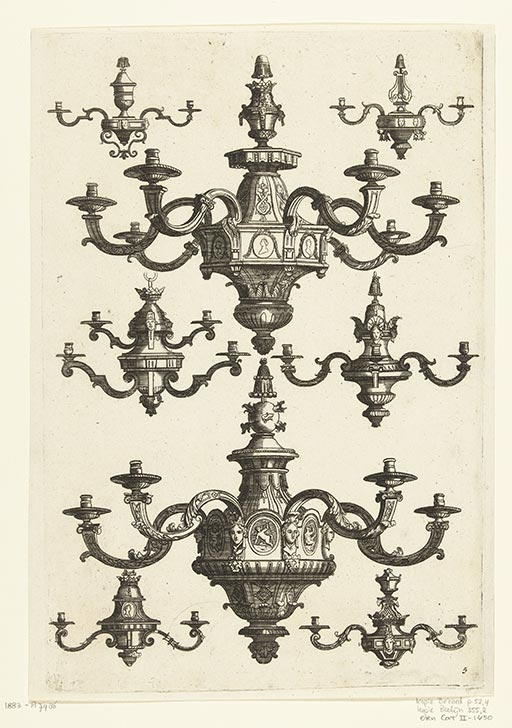

The Golden Room contains beautifully carved, gilded decoration with shells, decorative masks, acanthus leaves and scrollwork. Designs by the French artist Jean Bérain (1640-1711) probably served as a source of inspiration for the decoration.

Differences

It is striking that the same decorative features are sometimes finished differently. Some masks are very expressive and detailed, while others seem plain and impersonal. It looks as if they were produced by various different craftsmen.

Gilding

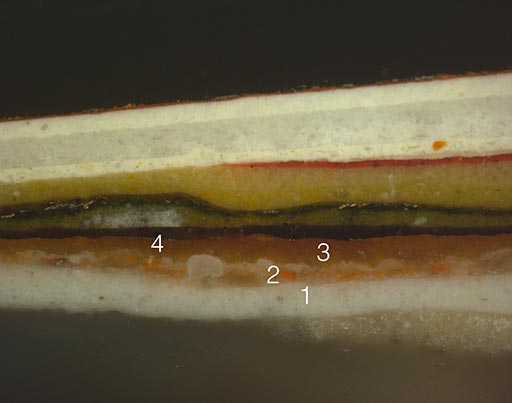

Gilded areas are built up as follows:

1. pale grey paint of the wall

2. orange paint layer of white lead, red lead, chalk and some fine black pigments

3. oil-rich paint layer of yellow earth, a so-called mixtion, which forms a foundation layer for the gold leaf

4. wafer-thin gold leaf

Mixtion or oil gilding gives a slightly matt finish, which is why it used to be known as ‘matte gold’.

Fireplaces

Fires were lit in the fireplaces during gatherings. A cast iron hearth plate on the ground would have protected the wooden floor. When the fireplaces were not in use, a decorative fireback probably sat in the chimney opening.

Graffiti

Behind this grisaille (a painting in various shades of grey) is some 18th-century graffiti: a sketch on the wall of a decorative detail in black chalk. Similar decorative details appear above the frames of the mantle paintings and flower pieces, but they are missing from the grisailles themselves. The drawing makes it clear that the detailing was also intended for these. Above each of the grisaille frames are small nail holes in the woodwork where these ornaments were attached.

The left and right-hand side of the drawing are different, as was often the case with designs for decorative details.

The left and right-hand side of the drawing showing two different options.

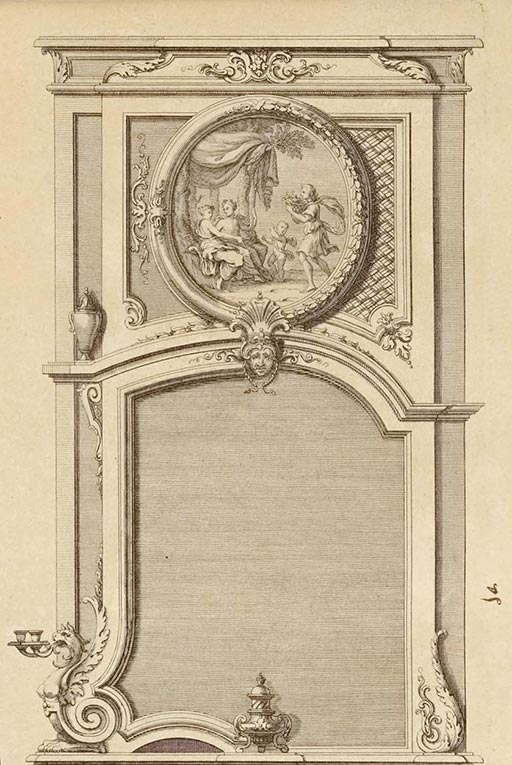

Design by Jean Bérain with a decorative mask. The left and right-hand sides of the print each show a different option (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam).

Above each of the grisaille frames are small holes (now filled in) where the ornament was once attached.

Wall Sconces

The current wall sconces were introduced in 1984. They are based on the wall brackets in Enkhuizen’s town hall, dating from around 1685. But around 1715 a different kind of lighting was popular: sconces with one or more candlesticks in front of a small mirror. They cast more light thanks to the reflection of the candlelight in the mirror. The mirror sconces were probably attached to the pilasters to either side of the grisailles: there are still small nail holes visible in the wood.

Chandeliers

The present-day chandeliers are replicas of examples found in Paleis Het Loo and were hung in 1984. The type of chandelier that hung here around 1715 is unknown. At that time, eight-arm chandeliers were very fashionable for important rooms.

Mirrors on the chimney breast

The pilasters on the chimney breast must have originally been decorated with mirrors too. This is often seen in 18th-century designs.

Grisailles

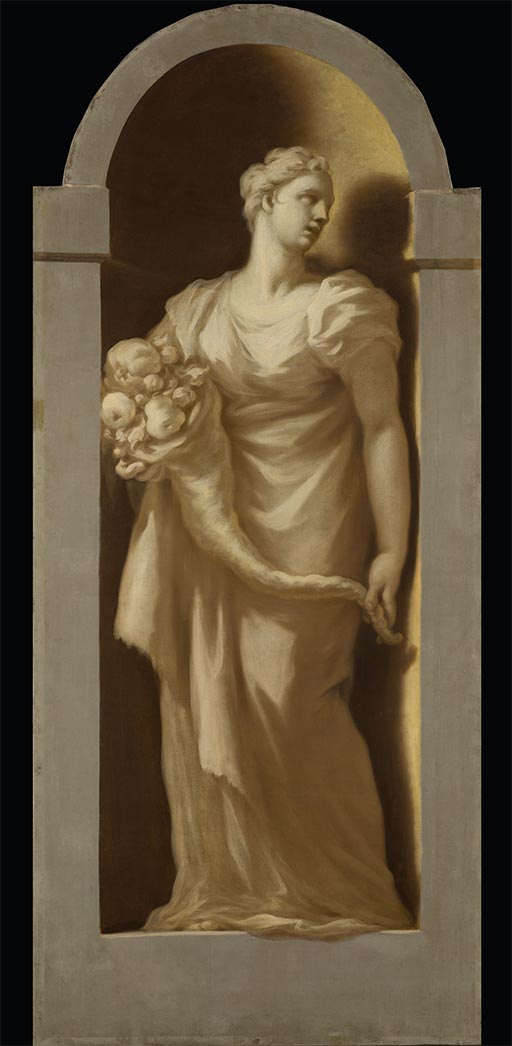

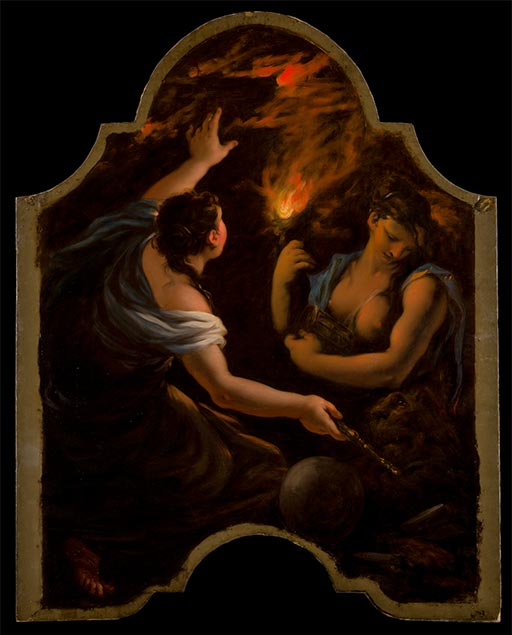

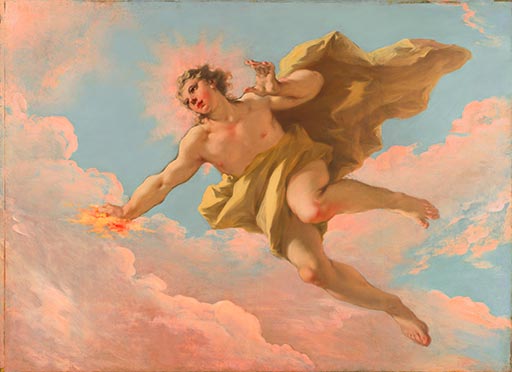

Pellegrini painted the four canvases on the walls in shades of grey only. This is where their name comes from: grisailles. As a result they look like stone niches with marble statues of the four elements: earth, fire, light and water. The paintings were originally arranged differently than they are today.

As the paint has aged, the front of the painted niches has become greener, more blemished and darker. But when they had just been completed, they better complemented the warm grey of the statues and pale grey of the walls.

Flower pieces

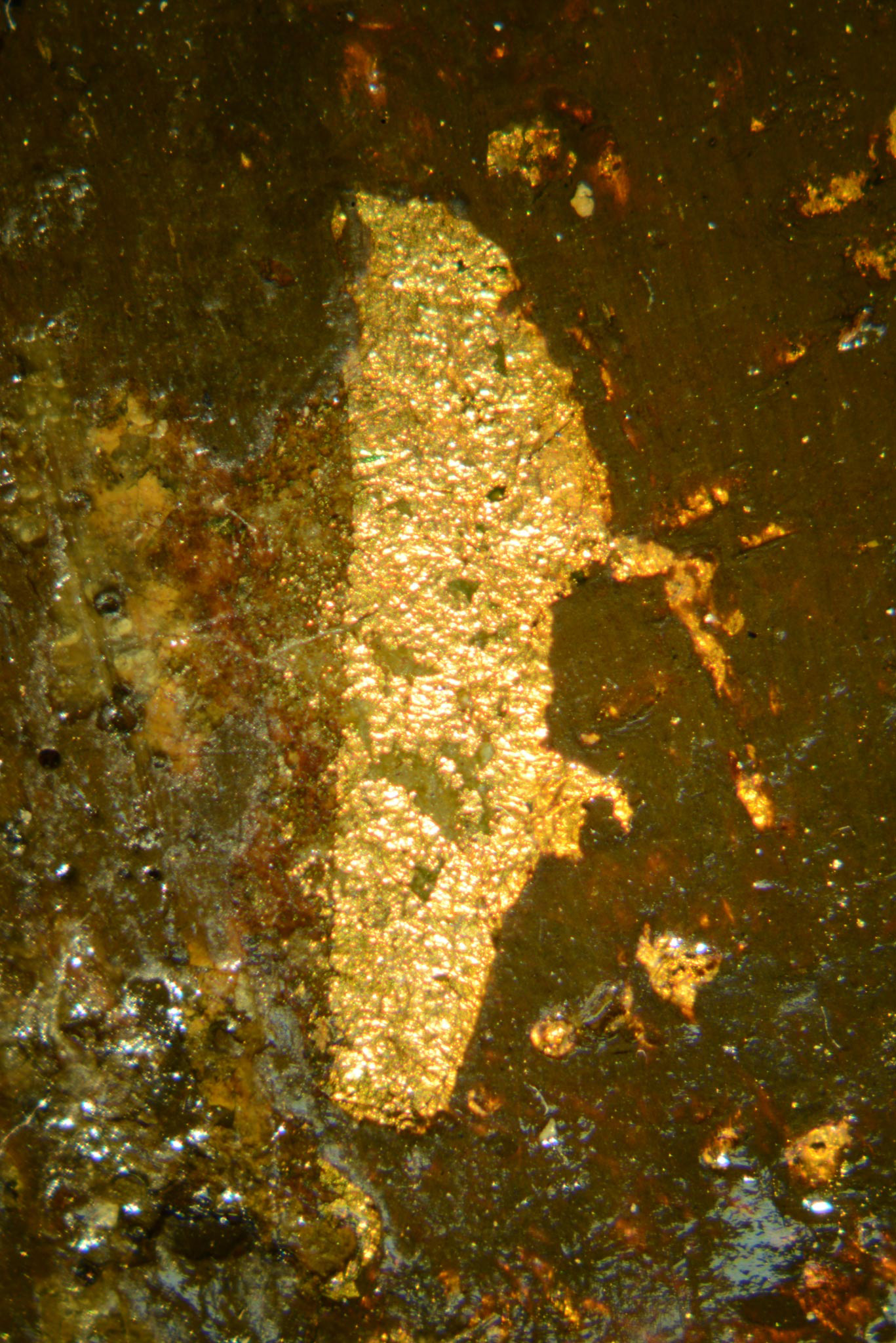

The flower pieces originally looked very different. The backgrounds were a golden colour, as were the containers in which the flowers are arranged. Pellegrini used brass leaf for this. The containers were probably suggested on top of this with only a thin layer of brown paint. Over the course of time the metal has largely disappeared, which is why the background has been overpainted several times. The paint suggesting the flower containers was possibly removed during a past restoration. The flowers and leaves have also become rather faded as a result of earlier cleaning efforts.

This flower still life by the Hague flower painter Caspar Verbruggen I (Palais Dorotheum, Vienna, 2014) served as the model for the reconstruction of the container.

Overdoor paintings with flowers were often painted on foil in the early 18th century, like this example in Huis Schuylenburch in The Hague (1715). The background has survived well in this instance because gold rather than brass leaf was used.

Microscope image of the background, with a small area of brass leaf that has survived.

Digital impression of one of the flower pieces against a gold-coloured background with vibrant flowers and recognisable leaves in a flower container.

Mantel paintings

The mantel paintings are in relatively good condition, even if the dark background, blue paint and skin tone shadows have become darker. The skin tones have also become more transparent, which means that the brown base layer shimmers through more than it should.

In the digital reconstruction these effects of time have been corrected, giving the figures a more pronounced three-dimensional effect. The small sailing boat behind Venus and Vulcan is also more obvious.

Ceiling Paintings

The ceiling paintings depict Aurora (centre), who is driving away Night to make way for Apollo, god of the Sun. These paintings have become greatly discoloured over the years. The blue (containing the pigment smalt) and pink in particular have faded. The paint layer has also become worn as a result of earlier cleaning efforts. This has been corrected in the digital reconstruction. The colours were originally much brighter, as with many other Pellegrini works.

Detail of The Night during varnish removal. On the right the varnish is still present. On the left, at the bottom, it is evident that the pink and blue paint has survived better in areas where it was protected by the frame.

The vivid colours have survived well in this oil painting by Pellegrini.

The colours in these frescoes painted by Pellegrini in the Villa Alessandri near Venice (circa 1704) are very vivid.

Digital impression of the original appearance of The Night.

Digital impression of the original appearance of Aurora.

Digital impression of the original appearance of Apollo.

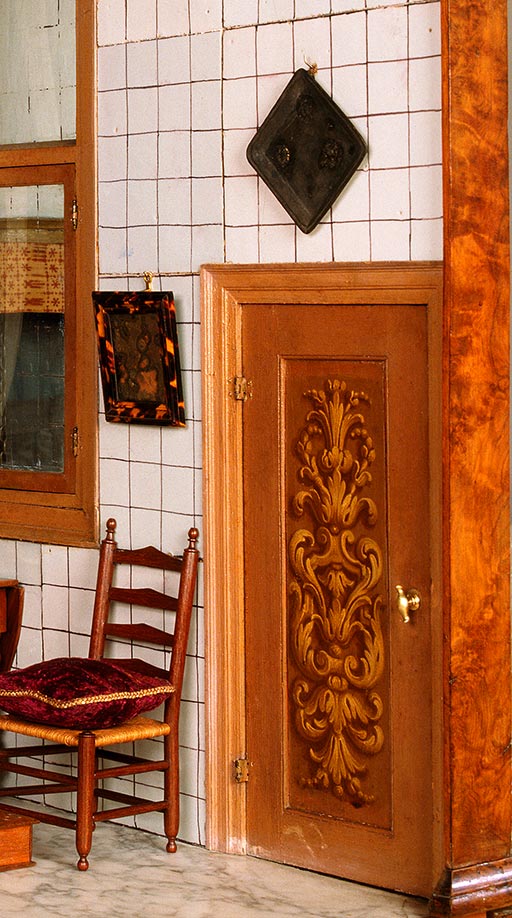

Door furniture

The room’s original door furniture has not survived. Hinges and doorknobs from other rooms from the same period were used as models for the digital reconstruction of the Golden Room.

Golden Room Reconstruction

The most beautiful space in the Mauritshuis is the Golden Room. After the devastating fire of 1704 this reception room was decorated in the then prevailing Louis XIV style. It became an impressive ensemble with an abundance of scrollwork and gilding, along with wonderful wall and ceiling paintings by the Venetian artist Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini. Over the years much about the Golden Room has changed. But how did it look originally? You can now find out with this digital reconstruction.

This digital reconstruction is based on recent scientific research:

- research into the colour finish and creation of the digital reconstruction were undertaken as part of the project From Isolation to Coherence: an Integrated Technical, Visual and Historical Study of 17th and 18th Century Dutch Painting Ensemble led by Margriet van Eikema Hommes.

Five-year research project (2012-2017) financed by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (Vidi grant) based at the Delft University of Technology. The Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands and the Rijksmuseum are project partners.

- research into the original colours in Pellegrini’s paintings: Mauritshuis conservation studio in partnership with Shell Technology Centre Amsterdam, as part of the joint project Partners in Science.

Credits

Digital reconstruction production: DeRoDe3D. Digital impressions of the original appearance of Pellegrini’s paintings: L. de Moor.

Advisors: Willemijn Fock, Johan de Haan, Ruth Jongsma, Paula van der Heiden, Henny Brouwer, Arie Pappot, Carol Pottasch, Quentin Buvelot.

This digital reconstruction was made possible thanks to financial support from the Johan Maurits Compagnie Foundation.

Impressions of the original appearance of Pellegrini’s paintings were made possible thanks to financial support from the project From Isolation to Coherence.